Like a Kid in a Candy Store

/As a relatively young scientist, one of the most exciting parts of my job is the moment I first get some new data. In a few months I may very well be sick of looking at it, and annoyed that it isn't more clear. But, the anticipation of the first look at something that I know contains the answer to an important question reminds me why I am a scientist. It has the power to offset weeks of frustration or tedium and reinvigorate the scientific process. Today I had one of those moments.

It doesn't happen with all new data. Some data come gradually as you gather time point after time point. Other data come quickly. Neither of these are as exciting as something that you had to wait for, that you weren't sure would work, and that you knew you would only get one shot at. When you work in the deep sea you don't always get to re-run an expreiment if it doesn't work. When you work in the deep sea, and you build your own sampling devices from scratch, you pretty much keep your fingers crossed from the time you deploy to the time you retrieve. My fingers have been crossed for two years.

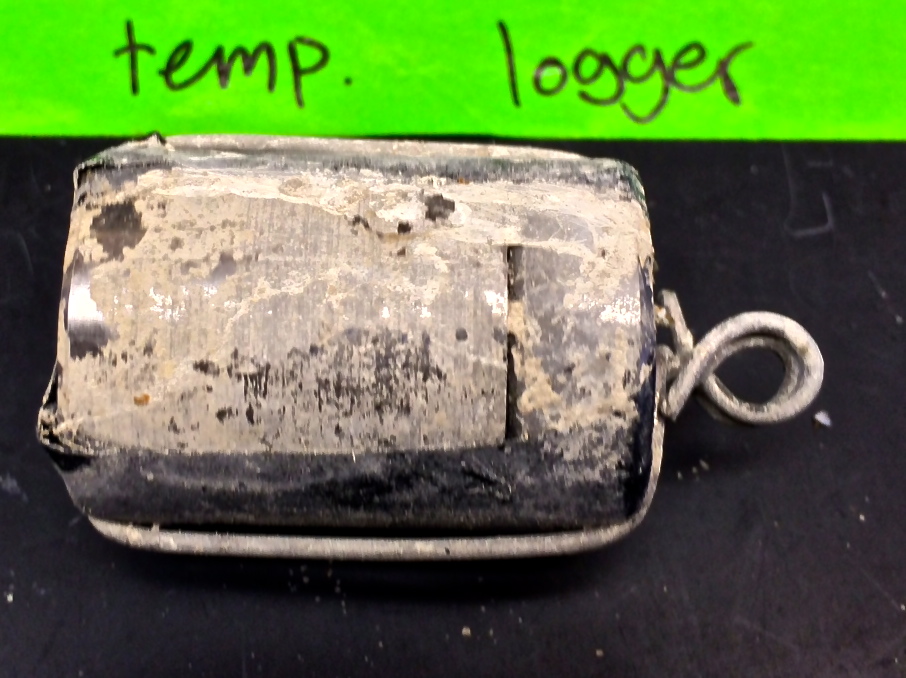

The strange looking thing in the picture above is a titanium pressure housing that we designed to hold a small battery-powered temperature logger called an ibutton. It protects the ibutton from the crushing pressure and toxic chemicals found at hydrothermal vents. It has lived inside an experiment of mine at a site on the Juan de Fuca Ridge in the eastern Pacific for the last two years. Its time sitting in a hydrothermal vent is why it looks white and crusty, and also why it smelled like something between rotten eggs and death. (What can I say? Dirty smelly science is, in fact, the best kind.) I was supposed to get it back, along with two others like it, over a year ago. But, changes to research cruise schedules prevented that. Luckily, we had programmed it to take readings slowly enough (every 9000 seconds or 2.5 hours) so that the battery would last a few years... just in case.

Today I got these little guys back, via FedEx, from a collaborator who was awesome enough to pick up my experiments for me while they were out at sea. I didn't know whether the pressure housings would successfully protect the temperature loggers. I didn't know if the temperature logger's batteries would last as long as they were supposed to, or if they would work properly on the bottom of the ocean. I didn't even know if my experiments would still be there after 2 years. So today when I went to download the data from the temperature loggers, and I saw strings of thousands of temperature measurements, I got excited. Kid in a candy store excited. There may have been dancing.

These temperature data are not groundbreaking. They will not cure cancer or help solve climate change. What they will do is provide a picture of how temperature fluctuates at one deep sea hydrothermal vent. It is a small piece to a big, complicated puzzle - one of those thousand piece puzzles with no edges or corner pieces that consist entirely of repeating shapes and similar colors. These sites are hard to get to, so most of the data we have consists of brief snapshots collected during research cruises years apart. These temperature records will provide environmental context for biological data I am slowly gathering from the experiment of which they were a part.

It is a long way from these data to a better understanding of what microbes are doing in vent environments, and even farther to how those activities fit into global biogeochemical cycles, which is what I am ultimately shooting for. However, today was a small step, and therefore it was a good day in science-land.